“Most of the instruments required in [Chinese] ritual music

have a particular kind of musical notation adapted to the exigencies of their

conformation. For instance, a piece

written for [Qin] presents a complicated combination of strokes difficult to

learn and decipher. Still it is an

ingenious and abbreviated kind of notation.” – J.A. Van Aalst, Chinese Music

I can still

remember sitting in the upstairs music room of my elementary school where the

teacher described a half rest as a top hat and a whole rest as a hole in the

ground. I remember taking up trumpet in

middle school and learning to use a musical instrument to create music

according to such written representations.

I remember joining the jazz band in community college and dedicating

free time during the summer before to learning to read the bass clef, which I

had never needed to know for trumpet, so I could be a proper bassist. All along, I assumed that this was the way

that music was to be written, and never did I imagine that there might be other

systems of recording sounds on paper.

|

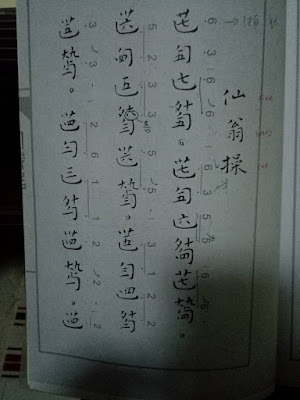

| A piece of Guqin music. |

The system

of writing Guqin music is very fitting to the culture which the instrument

comes from. If someone were to string

together several Chinese words and among them include a single character that

was actually for Guqin musical notation, the western eye would have much

difficulty deciding which was the odd man out.

Despite this, many Chinese people might look at it and be very confused

by the character which they were unable to read. The basic character strokes denoting finger

plucking techniques (right hand) were presented in this post: Characters Representing Right Hand Finger Techniques. These strokes are the foundation upon which

more information is built through a use of radicals, similar to Chinese

orthography, so that each character in the tablature represents one musical

note created through actions of both the right (plucking) and left

(pressing/sliding/tapping) hands. Guqin music is written as Chinese used to be, that is top to bottom and right to left.

There are thirteen inlaid dots

along the top of the body of a Guqin which are used to show the location of

notes, similar to the fretting and inlays on the neck of a guitar. The numbering used to represent these

locations in the tablature naturally use Chinese numbers: 一,二,三,四,五,六,七,八,九,十,十一,十二,十三.

The next

bit that one needs to know is character/radicals which represent the fingers of

the left hand:

|

| The left hand characters. |

The pinky finger is not used for Guqin, whether on the right

hand or on the left. The character

representing the pointer finger changes to the radical form of 人

when used in musical tablature. For the

ring finger, only the top portion of 名is used (see below).

When

reading a piece of Guqin music, one character made of several radicals

represents one note to be produced. Each

radical tells the player something about how to make the note, e.g., which

finger of the left hand to use, which location to press down on the string, how

to pluck with the right hand, and, of course, which of the seven strings should

be plucked.

Timing is also represented in modern Chinese music, though there was a time when this was not the case, but an explanation of that will be saved for another post.